Introduction

One of the primary objectives of Russian propaganda and information influence in the Polish information space is to undermine interstate relations. The destruction of Ukraine’s relations with neighboring states is a strategic goal of Russian propaganda as Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine begins on February 24, 2022. A wide range of information influence tools aimed at the political process, both domestic and foreign policy, are used to this end. As a result, public opinion is distorted, and threats to national security, particularly in the information sphere, are created.

The topic of Polish-Ukrainian relations is a particularly relevant area of Russian propaganda aimed at disintegrating Kyiv and its partner countries. The military, diplomatic, logistical, and economic assistance provided by Warsaw is an invaluable resource for Ukraine’s resistance in its conflict with the aggressor. The border with Poland serves as a vital transit point for military equipment and weapons, as well as a route for exporting Ukrainian goods to the EU. As a result, in the context of the war, the Kremlin’s strategic goal is to destroy relations between Kyiv and Warsaw, as this would be a direct blow to Ukraine’s military and economic rear.

At the same time, Poland has taken in the greatest number of Ukrainians who have been forced to flee their homes due to Russia’s invasion. Since the outbreak of the full-scale war, more than 12 million Ukrainians have crossed the border into Poland. According to the most recent data, approximately 1.2 million Ukrainians live in Poland, with nearly 40% planning to stay after the war ends. Such statistics point to a wide range of opportunities for manipulation and information provocations in the context of the two countries’ domestic relations. Moscow encourages and escalates conflict between Poles and Ukrainians and works to distort the image of the two countries and peoples in each other’s eyes. The Kremlin’s interest is in undermining trust in Poland as a safe place to live and work, in order to undermine Ukraine’s social stability.

Russia is also making significant efforts to undermine the two countries’ national memory policies. This area of Russian propaganda is part of the Kremlin’s state ideology, which is based on World War II mythology. As a result, Moscow is actively exploiting historical issues in Polish-Ukrainian relations to appeal to the right-wing radical sentiments of a segment of Polish society. Such Moscow activities have the potential not only to stifle dialogue between Warsaw and Kyiv, but also to exert direct influence on Poland’s domestic political landscape.

Given the importance of the study, the goal of our research is to thoroughly examine the structure and specific features of Russia’s information influence in the Polish media space, to clarify the peculiarities of Russia’s information policy in the plane of Polish-Ukrainian relations, and to investigate the manipulation potential of strategic topics for bilateral relations between Ukraine and Poland.

The following research objectives are determined by this goal:

- Identify meta-narratives in the Russian propaganda system and their manipulative potential;

- Outline the role of Russia’s information influence in the context of the Kremlin’s foreign policy;

- Identify metanarratives in the Russian propaganda system and their manipulative potential;

- Identify the existing opportunities and potential of Russian information influences for further promotion in the Polish information space;

- Identify information narratives aimed at undermining Polish-Ukrainian relations and their manipulative potential;

- Apply and test the method of expert evaluation of news headlines on the topic of Ukrainian-Polish relations;

- To establish a list of topics that have the most significant impact on bilateral relations between Poland and Ukraine.

The study’s methodological tools include the following methods: descriptive method, problem-categorical analysis method, socio-cultural analysis method, discourse analysis method, and expert evaluation method.

Section 1: The Russian Federation’s Information Influence as an Element of the Kremlin’s Foreign Aggression

1.1. Russia’s information influence and its role in advancing Russian interests abroad

Globalization processes that have resulted in international space interdependence have been accelerated by advances in technology and communication. As a result, one country’s communication and information presence in another has grown. This has aided both the general exchange of ideas and the spread of European values while also increasing EU countries’ vulnerability to Russian propaganda, which ideologically opposed the Western world, democratic way of life, and human rights.

Since 2014, Russia’s information influence in the world has grown with renewed vigour. This was preceded by the Ukrainian Dignity Revolution, which occurred in response to pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych’s refusal to sign the Association Agreement and Free Trade Zone between Ukraine and the European Union at the Eastern Partnership Summit in Vilnius. These events served as the foundation for the Russian Federation’s development of a new strategic content to fuel its expansionary policy toward countries that have historically been in Russia’s sphere of influence at various times, as well as to justify interference in the internal political processes of other states.

Thus, by portraying the Revolution of Dignity as a coup inspired by the „collective West” in Ukraine, Russia created an adaptive narrative whose internal logic could easily be used in other countries, if necessary, to discredit pro-European political courses, crack down on individual opposition politicians, and keep countries in its sphere of influence, with destructive information influence and propaganda being one of the tools used for this purpose.

The goal of the new round of Russian propaganda in the region was to interfere in the political processes of both Ukraine and other countries (mostly neighboring ones), as well as to discredit Ukraine in the international arena, as part of preparing the information space for a full-scale invasion through destructive information influences.

In this context, one of Russia’s soft power tools is destructive information influence. aimed not at projecting an appealing image, but at subjugation, as this phenomenon is understood in Russia. Thus, the spread of meta-narratives, narratives based on messages favorable to Russia, aims to influence public opinion in both countries and ensure Russia’s hybrid control over public sentiment, preferences, and political behavior.

According to the study’s authors, Russia’s increased information influence and propaganda against individual countries is intended to both stir up contradictions within society and strain relations with partners and neighbors, as well as discredit such a country in the international arena and in political organizations or entities of which it is a member. Following Russia’s full-fledged invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, such a subversive strategy in the context of information hybrid threats manifested primarily in relation to Ukraine’s neighboring states, which were the first to receive thousands of Ukrainian refugees and then became logistical hubs for Ukraine. These Russian actions endanger not only the national security of the countries that are the targets of destructive information influences, but also the national security of Ukraine, because they harm relations between strategic partners.

On the eve of European Parliament elections, Russia’s destructive information influences intensify in order to increase disagreements in Europe. From the standpoint of changing political cycles, 2023 appears to be no less difficult, as most of Ukraine’s neighbors are holding national election campaigns that will lead to European elections in June 2024. These circumstances foster an emotionally favorable environment for the exploitation of basic needs, particularly security, fears, and emotions. Thus, the period 2023-2024 appears to be critical for countering destructive information influences, both in the context of Russia’s full-scale aggression against Ukraine and in the implementation of political processes.

Returning to Poland, the subject of this study, Russia employs the narrative that „Poland has become more impoverished since joining the EU than during the communist era,” thereby implementing an anti-Western meta-narrative. The Kremlin also used narratives to instill disbelief in democracy and European values in Poles, as well as to spread xenophobia and a sense of „inferiority” in comparison to residents of so-called „Old Europe”. Interestingly, in Russian propaganda content, Poland is portrayed in a negative light for the EU in order to create a negative image of the country in the eyes of its Western partners.

1.2. Russian propaganda’s adaptive metanarratives and their manipulative potential

The primary goal of Russia’s destructive information influences is to maintain control over the target audience’s behavior and consciousness. The Russian information influence technologies system includes metanarratives, narratives, and information messages with varying degrees of veracity. A metanarrative, as a type of communicative influence, aims to arrange the elements of reality and organize these elements into a story that develops in a short (or long-term) historical perspective in relation to the past and the future, striving for a culmination and forming the appropriate attitude of the audience, which will further determine the appropriate behavior.

All of this provides manipulative potential via abstraction in relation to a specific point in time as well as the possibility of substituting the future for the past. According to the authors, one of the conditions for the destructive effect of information influence is the time parameters that a metanarrative can narrow and expand. This metanarrative feature can be interpreted in light of P. Ricker and D. Carr’s general concept, which sees the narrative structure as similar to the goal-setting structure.

In political realities, metanarrative technologies can include inciting „historical revanchism” by appealing to historical, political, or stability greatness. Another powerful example of metanarrative in the context of time distortion is the promotion of the „Soviet past.” (In the context of Ukrainian-Polish relations, examples).

Metanarratives are adaptive in nature, which means that they can adapt to different information spaces and contexts because they are sufficiently abstracted from political and social specifics. One of the conditions for manipulative potential is metanarrative adaptability to a specific communication context.

Metanarrative forms are widely used by Russian propaganda in different countries’ information spaces, taking into account local peculiarities in different political, social, or economic contexts, in order to shape the audience’s attitude toward certain events and influence the audience’s future behavior. Each metanarrative is realized through a collection of specific narratives, which are made up of information messages of varying veracity.

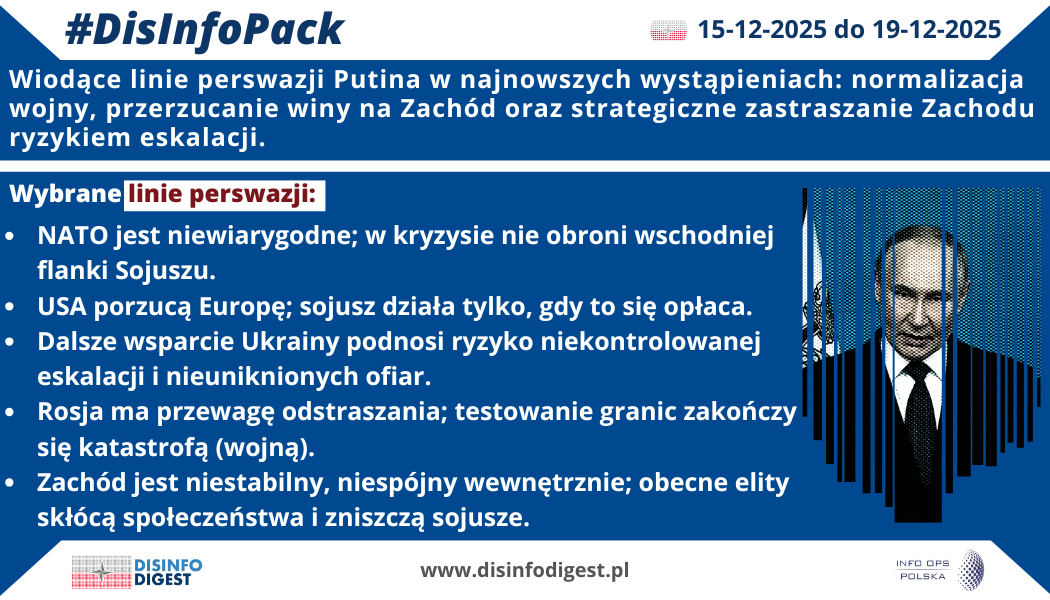

Before the full-scale invasion, one of the metanarratives of Russian propaganda accompanied the diplomatic processes between Russia and the United States against the backdrop of escalation towards Ukraine and NATO. The metanarrative was used to prepare the information space for NATO to accuse Russia of war.

The metanarrative was implemented in various countries by demonizing the North Atlantic Alliance in various countries through topics relevant to local audiences. In Ukraine’s neighboring countries, such as Poland and Romania, „anti-NATO” narratives spread messages that NATO was unable to protect its members.

On the eve of a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia launched a large-scale information campaign claiming that NATO should return to the „borders” of 1997, i.e., expel the Baltic states, former Warsaw Pact countries, and new Balkan members from NATO. Russia broadcast a narrative about NATO’s inability to confront Russia militarily and its inability to protect its partners as part of the information operation. Simultaneously, Russian propaganda persuaded its domestic audience that NATO posed a threat to Russia.

Another meta-narrative of Russian propaganda that can be seen in various countries is the charge of „Russophobia.” Russia has used this construct to justify interfering in the internal affairs of other countries, including as justification for a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Furthermore, the „Russophobia” meta-narrative has been used to discredit politicians, activists, and journalists through personal attacks.

The metanarrative of „Russophobia” can be described as a universal propaganda tool that Russia employs quite effectively, both in terms of information influence, diplomacy, and active measures provided by Russian government-affiliated organizations abroad. Thus, meta-narratives in the Russian Federation’s communication presence in the foreign information space ensure that Russia’s strategic interests are promoted. Thus, manipulative potential is a set of capabilities that use state propaganda to shape the audience’s perception of specific events by abstracting and concretizing the metanarrative and narrative in accordance with the local communication context and the Russian Federation’s interests and “soft power”

In this study, manipulative potential is regarded as the primary indicator of manipulative information influence, with the hidden goal of controlling society’s political process, political behavior, and political aspirations. This definition corresponds to the three levels of effectiveness of manipulation as a tool for controlling the target’s 1) thoughts, 2) behavior, and 3) emotions.

In this case, the object of manipulation serves as a passive means for the manipulator to realize hidden intentions and satisfy needs rather than as a full participant in the communication process (addressee – recipient). Such power implies the impossibility of a retaliatory reaction from the object of manipulation. The ultimate goal is to change the object of manipulation’s goals, aspirations, desires, and points of view through manipulation’s influence on the cognitive sphere.

Section 2: Russian propaganda on Polish-Ukrainian relations

2.1 Russia’s destabilizing information influence in Ukrainian-Polish relations

The Kremlin’s information influence in the international arena differs significantly from the goals of Western democracies. The focus of the Kremlin’s influence on foreign audiences has shifted significantly in the face of growing authoritarianism in Russia’s domestic political system. Moscow has progressed from attempts to broadcast appealing images from the spheres of culture, values, or political ideals to manipulating the target audience and attempting to discredit the achievements of the democratic world.

Russia actively used soft power from the turn of the millennium up until 2010. In the late 2000s, Moscow attempted to rebuild the infrastructure of Russian soft power in Poland against the backdrop of attempts to reset Russian-Polish relations. At the institutional level, it was assumed that the Russian-Polish Center for Dialogue and Consent in Russia and the Polish-Russian Center for Dialogue and Consent in Poland would lead the Russian hybrid influence.

Simultaneously, Russia attempted to integrate through Polish academic circles. For example, in 2019, the project „Poland and Russia: Intergenerational Dialogue” was implemented to foster cultural, scientific, and educational interaction between Russian and Polish students and teachers. Representatives from the Ural State Pedagogical University, Kazan Federal University, the Ural Federal University’s Boris Yeltsin Specialized Educational and Research Center, the Stanislaw Piagon Higher State Vocational School (Krosno, Poland), and the Jagiellonian University (Krakow, Poland) took part in the project.

Through cross-border cooperation projects, primarily in the fields of culture and tourism, Moscow has attempted to improve its image of Russia in the information sphere. For example, in 2020-21, the Presidential Grants Fund (RF) supported the following programs: Gizycko and Soviet – Cooperation to Develop the Preservation of Historical, Cultural, and Natural Heritage in the Border Area; 2 Ships – One Sea. Soldek and Vityaz: The Maritime Heritage of Poland and Russia”, the International Sailing Regatta Cup of the Three Governors, which traditionally involved representatives from Poland and the Kaliningrad region of the Russian Federation.

However, in the context of recent confrontational relations between Warsaw and Moscow, these projects are rather insignificant. To avoid the practice of repeatedly resetting the agenda, a policy that had been hindered by factors like Vladimir Putin’s re-election to the presidency in 2012, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in 2014, and the rise of a conservative government led by „Law and Justice”, the Kremlin has now embraced a „гострої сили” strategy (Sharp power). This is a method of conducting a state’s foreign policy based on manipulative hybrid influence on another state’s political system.

With the start of the Dignity Revolution in Poland in 2014, Russia intensified its anti-Ukrainian propaganda. Furthermore, to undermine Poland’s information space, Russian propaganda disseminated messages that portrayed NATO and the EU negatively, distorted the foundations of Western values, and denied and discredited the concept of a pan-European community.

Since 2017, Russian propaganda in Poland has focused on specific target audiences (TAs). They primarily targeted young people (the most socially integrated segment of society) and provincial residents (who are more likely to hold conservative views and have a strong sense of history). Polish intelligence services stated in 2020 that Russian propaganda aims to change public opinion about the Soviet Union’s role in World War II and the signing of the so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact by distorting history.

According to the VoxCheck fact-checking project’s „Propaganda Diary – 2022: The Year of Russian Disinformation in Europe,” Poland has become „the most targeted country for Russian propaganda, accounting for nearly a quarter of all disinformation cases” amid Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

It should be noted that Russia’s opportunities to influence Polish society in the information space are limited. This is due to two major factors.

First, Russia’s main information dissemination platform (Telegram) remains in Russian, despite Poland’s high barrier to the Russian language. According to sociologists, only 8% of the Polish population understands Russian well enough to use Russian media.

Second, the Kremlin’s information capabilities have been diminished by the EU’s ban on state Russian broadcasting in March 2022. The broadcasting of Sputnik and RT/Russia Today, Rossiya24, TV Center International, and RTR Planeta was halted as a result of the sanctions. These media outlets are barred from broadcasting in the EU via cable networks, satellite, and the Internet.

Telegram, which is one of the primary channels for disseminating propaganda and information influences, particularly regarding Russian aggression against Ukraine, is also not popular enough among Poles to have the potential to shape national public opinion. As of 2022, Telegram had a 7% audience among users of messengers and social networks who used the services of Polish providers. Simultaneously, Telegram continues to be a platform for attracting people from Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine to keep them in the communication context of Russian propaganda, which creates the preconditions for more complex provocations. For example, posting leaflets with Wagner PMC symbols or the dissemination of provocative information, fakes, and disinformation against Ukrainian refugees that reaches an audience in Ukraine and thus serves as a potential source of tension between communities in both countries.

Furthermore, in order to influence Polish society, Russia is attempting to use Polish-language information and communication platforms that position themselves as right-wing radicals (kresy.pl, nczas.com, nacjonalista.pl, wprawo.pl) or „out-of-system” platforms that de facto support pro-Russian views (Mysl Polska, Instytut Spraw Obywatelskich, Geopolityka. net, Niezalezny Dziennik Polityczny), Facebook and YouTube channels, as well as through Russian information resources with Polish-language versions, such as the portal targeting the Russian-speaking population of the Baltic States, Rubaltic.ru.

2.2 Russian narratives in the context of Polish-Ukrainian relations

Russia is attempting to influence both Polish and Ukrainian societies at the same time in order to sow discord and distrust between the two countries. At the same time, Kremlin ideologues are attempting to polarize public opinion in both countries on issues of common interest: integration of Ukrainians in Poland (domestic conflicts), memory politics (historical perspectives), and economic rivalry in domestic and foreign markets (the issue of grain exports).

Despite sanctions imposed on the Russian media industry in the EU (in particular, in Poland) and in Ukraine, the role of Russian state media remains leading in shaping narratives and communication strategies in the „hard power” paradigm against Poland and Ukraine. Within the framework of the use of „hard power” against Poland and Ukraine in the context of bilateral relations, the leading place is occupied by the state-owned RT holding, which was founded in 2005 to provide a „Russian view of major world events” to the global audience and is fully funded from the Russian state budget.

Despite different approaches to conceptualizing information influences and, in particular, propaganda, it is reasonable to assume that in the case of the Russian Federation, the goal of state propaganda is to spread doubt rather than to convince the audience. The state broadcaster RT’s motto is „Ask More”. RT’s strategy, according to Anne Quaranto and Jason Stanley, was designed to create doubt rather than information, relying on the classic propaganda technique of undermining trust in democratic institutions.

According to British researcher Tobias Redington, the state-owned Russian holding company RT’s information activities are disguised, indicating that the holding company serves as Russia’s information weapon. The disguised nature of RT’s information activities stems from the fact that broadcasting during a „critical” moment differs from broadcasting during a „non-critical moment.” In other words, during times of crisis or political escalation in the international arena, the channel spreads narratives favorable to Russia (creates doubts) based on false information messages to mislead the audience and maintain the Russian authorities’ official position.

At the same time, in „non-critical moments”, information (communication) activities are aimed at building „trusting” relationships with audiences to exploit this trust in the future in Russia’s interests.

Based on this, the nature of RT’s information activities is decisive in the overall system of pro-Russian narratives, which are further disseminated through the entire system of communication channels involved in the use of „hard power” by Russia, and analyzing RT content is critical in developing an understanding of the key approaches to Russia’s targeted information operations during a crisis.

Let us highlight the key narratives that Russia incorporates into Polish media in order to discredit Ukrainians and incite ethnic hatred.

Narratives aimed at instilling hostility toward Ukrainians in Polish society:

Ukrainian refugees. Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, discrediting Ukrainian refugees has been one of Russia’s main narratives, which has largely focused on Poland as one of the countries that has sheltered the greatest number of Ukrainian refugees. This narrative was supported by disinformation campaigns and a series of fakes about governments caring about Ukrainian refugees more than their own citizens, that real refugees from the war zone went to Russia, that Ukrainian refugees are a burden on the economy, that refugees from Ukraine are in fact economic migrants, that refugees do not want to look for work and work, that refugees violate social norms and behave badly, that Ukrainian refugees force Europeans to speak only Ukrainian and therefore are „Nazis.” The most widespread messages of Russian propaganda relate to the following topics:

- Poles are being pushed out of the labor market by newly arrived Ukrainians. The Russian media, for example, actively cited data from a survey conducted by IRCenter in collaboration with the Newseria agency (results published in July 2023). According to them, one-third of Poles believe that Ukrainian refugees take their jobs, and 33% believe that Ukrainians take the places of Polish citizens in schools and universities.

- Ukrainians despise Polish culture and history, inciting domestic strife. This information influence vector combines elements of historical past manipulation and the topic of Ukrainian refugees. According to one report, Ukrainians allegedly demanded that Poles consistently yell „Glory to Ukraine!” It was also claimed that the slogan is associated with the Volyn tragedy in Poland and that when young Poles refused to comply, Ukrainians kicked them. According to the Warsaw Police Department, 13 people were identified, none of whom were Ukrainian citizens. Nobody sought medical help or reported the crime.

- Ukrainians have an immoral way of life. The manipulation of information about the growing number of AIDS cases in Poland is one example of this narrative. According to Russian media, „…some visiting Ukrainian women, having HIV infection, go to work as escorts or have affairs with local men, after which the latter also become carriers of this infection, which they then pass on to their women”.

- „Fake” Ukrainian refugees. Since February 2022, there have been 1-1.5 million Ukrainian refugees in Poland who have gained access to material assistance, the healthcare system and labor market, the opportunity to educate children in schools, and so on, and Russian propaganda is attempting to use the migration crisis to create the impression in society that Ukrainians came for privileges rather than to flee the war. For example, Russian media frequently cited a discriminatory statement by Niezalezny Dziennik Polityczny (NDP) journalist Maker Halasz that Ukrainian refugees want free housing and medical care, which is illegal.

Thus, the Russian media’s main strategy is to magnify individual excesses that are not systemic to all ethnic Ukrainians living in Poland. It is also common practice to quote marginalized commentators who are little known in Poland on the Russian Federation’s largest state media platforms, giving more weight to provocative statements and their authors.

It is worth noting that Russia developed information manipulations on the topic of migrants and refugees in 2021, during the migration crisis inspired by the Belarusian and Russian regimes on the Polish border.

In the information sphere, the campaign sought to discredit the EU and, in particular, Poland in the eyes of Muslim communities, potentially leading to terrorist attacks in „revenge” for the „humiliation” of their fellow believers. Approximately 10,000 migrants seeking to cross the EU border were concentrated in Belarus during the period of maximum aggravation (November 2021). According to Poland’s Ministry of Internal Affairs, approximately 40 thousand illegal border crossings were recorded in 2021, but only 16 thousand in 2022. The border guard had recorded 19 thousand attempts by illegal immigrants to enter Poland as of August of this year. These dynamics clearly demonstrate the crisis’s man-made nature, which is being moderated from the Kremlin by Lukashenko’s allied regime.

Historical memory and historical revanchism. The narrative of Russian propaganda in the context of Ukrainian-Polish relations from a historical perspective aims to highlight the problematic aspects of the two nations’ relations. For example, Russian narratives emphasize that for 400 years, the main content of Russian-Polish relations was the armed struggle for Ukrainian territories. As a result, Poland’s „historical hostility” to Russia is said to be embodied in Ukrainian territory. The Kremlin’s demonstrative action to remove the Polish flag from the Katyn memorial in June 2022 is an example of the historical „rivalry” between Moscow and Warsaw in the context of Russia’s current invasion of Ukraine. In this way, Moscow is attempting to recreate images of past centuries’ wars between Russia and Poland on the territory of the modern Ukrainian state in cyberspace, which frequently becomes the content of Russian hybrid diplomacy in times of crisis.

The main goal of Moscow’s information campaign is to incite revanchist sentiments among the Polish far right in order to reclaim Western Ukrainian lands for Poland. For example, in September 2022, Russian media reported, citing Polish „politician” Konrad Rienkas, that „Poles want to return the property lost during World War II in Western Ukraine and have filed more than 1,500 lawsuits in courts”.

Coverage of pro-Russian actors’ media activities. The activities of pro-Russian figures who speculate on historical topics, cultivate interethnic distrust, use hate speech, radicalize various social groups, and pit them against each other in the context of the narrative of „Ukrainian dominance” (Marek Halasza, Leszek Sikulski, Confederation speakers) have been systematically covered by the Russian media.

The Russians actively covered the activities of the so-called „Polish Anti-War Movement,” which launched a campaign of street actions and public events under the slogan „To nie nasza wojna” („This is not our war”) in 2023. („The movement’s leader,” Leszek Sikulski, is portrayed in Russian media as „a force that does not agree with his country’s authorities’ anti-Russian policy”.

The Russian media also widely covered street rallies with anti-Ukrainian rhetoric. For example, the rally of the Monarchists (the party of the Confederation of the Polish Crown) on September 24, 2022, under the slogan „Stop the Ukrainization of Poland” in Warsaw was widely announced. The Russian media also actively quote and cover the activities of the party’s leader, Polish Sejm deputy Grzegorz Brown, in particular his „warnings” about the threat of „Banderaization of Poland”.

These facts demonstrate the complexity and hybrid nature of information threats that are the result of Russia’s organized active measures.

Narratives aimed at instilling hostility toward Poles in Ukrainian society:

- „Military intervention” of Poland in the Russo-Ukrainian war. The spread of messages on Warsaw’s intention to send Polish units to Ukraine began to circulate in the Russian z-segment of Telegram as early as the end of February 2022. Thus, this narrative is chronologically one of the first concerning Ukraine-Poland relations since the start of full-scale aggression.

Thus, this narrative is chronologically one of the first attempts to torpedo Ukraine-Poland relations since the beginning of full-scale aggression. Disinformation campaigns were aimed at causing panic and complicating the work of border checkpoints, through which millions of Ukrainian refugees crossed in search of shelter and safety during February-March of 2022. For example, one such news report stated that „Turkish military planes have flown to Poland ISIS militants and representatives of other terrorist organizations?”; „Polish private military companies are forming battalions for operations in Ukraine, which may include up to 20,000 mercenaries?” At the same time, representatives of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service claimed that the US and UK authorities had turned the territory of Poland into a „logistics hub” for transporting weapons and militants from the Middle East to Ukraine.

Over time, reports about Poland’s „participation” in the Russo-Ukrainian war were aimed at supporting the thesis that the Russian army is allegedly fighting „mercenaries of NATO countries, not the Ukrainian people” Accordingly, Russia launched an information campaign on the „involvement” of Polish security forces in punitive operations against pro-Russian citizens of Ukraine. In addition, Russian propaganda convinced Ukrainians that Poland is opening training centers where mercenaries are training before joining the battlefield in Ukraine. This is the way in which the Kremlin media „interprets” the establishment of the training center in Warsaw, dedicated to Polish paramedics who save frontline Ukrainian soldier’s lives.

- Poland „profits” from the war. One of the main goals of Russian propaganda is aimed at discrediting the supply of weapons to Ukraine, as well as at creating the impression of the unreliability of Polish logistics capabilities, which Ukraine relies on. With the beginning of a full-scale invasion, Poland became one of the main logistical hubs for the supply of weapons and deployed centers for the repair of military equipment.

In this context, Russian propaganda attempts to convince the Ukrainian audience that Poles benefit from the Ukrainian war, while their desire to assist Ukrainians is motivated by selfish interests.

The manifestation of this narrative is the „exposure?” of the American journalist Seymour Hersh, made on RT. According to him, since the beginning of the war, American weapons intended for Ukraine are stolen as soon as they arrived in Poland, Romania, and other European countries. A pro-Russian publicist claims that local commanders (at the rank of colonel) were personally involved in the resale of weapons on the black market.

- Another Russian tactic is to intimidate Ukrainian refugees by spreading rumors about the „radical policy” of the Polish authorities. In particular, Russian media influencers tried to create the impression that Warsaw intended to forcibly extradite male refugees to Ukraine for their subsequent conscription into military service.

In terms of the economic aspect, Moscow promotes the thesis about Warsaw’s self-interested motives, namely its desire to «establish control over the most promising sectors of Ukraine’s economy, primarily over agriculture. Poland invests in the creation of transport infrastructure for the smooth export of Ukrainian food to Europe and other markets».

For example, the statement by the Deputy Minister of Finance of Poland Artur Sobony, regarding the possibility that Warsaw will become a «financial hub» for collecting funds directed to the reconstruction of Ukraine, was interpreted as Poland’s desire to steal money intended for Ukraine.

- “Polish occupation” Ukraine’s territory. The narrative about Warsaw’s plans to „occupy” western Ukrainian lands are inextricably linked to the reports of Poland’s military intervention. In this case, we can talk about the complexity and hybridity of informational influences of Russia due to their combination with active measures aimed at promoting the relevant narrative.

The fake on Warsaw’s aggressive ambitions was accompanied by regular informational provocations by the leader of the Liberal Democratic Party Volodymyr Zhirynovsky. For example, in 2014, a politician from the Russian Federation’s State Duma sent a letter to Poland’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs proposing to divide Ukraine’s territory. In his letter, Zhirynovsky suggested holding a referendum on joining Poland in the western regions of Ukraine. Hungary and Romania received similar offers.

Putin, Lavrov, Shoigu, Medvedev, Patrushev and other high-ranking Kremlin officials have participated in the disinformation campaign since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. The main speaker on the so-called “Polish threat” is Serhiy Naryshkin, head of the SSR of the Russian Federation. Russia’s top intelligence officer made at least six statements regarding Warsaw’s plans to occupy Ukrainian lands (April, June, July, November 2022; April, July 2023). So it should be stated – the informational influence on the topic of Ukrainian-Polish relations is openly provided by the highest political figures of the Russian Federation.

Within the framework of the “Polish occupation” of Ukrainian territories, Russia assigns a special role to the Lithuanian-Polish-Ukrainian brigade (LITPOLUKRBRIG). In particular, President Duda’s visits are often accompanied by “forecasts” about «secret negotiations» regarding deployment of the brigade in Ukraine as a measure of implementing the «new union» plan.

Section 3: The Manipulative Potential of Anti-Ukrainian and Anti-Polish Narratives Using RT, Russia’s Leading Propaganda Outlet

3.1.1 Methodology Description

The data set used in the study to analyze the manipulative potential was news headlines published on RT’s main propaganda website, which coordinates broadcasting to foreign audiences. The analysis used news headlines from February 24, 2022, to September 30, 2023. The search for news headlines relevant to the study’s topic was conducted using keywords, yielding a sample of 1074 news headlines published on RT’s main website in Russian. According to the study’s authors, because most readers focus on scrolling through the news feed, news headlines fully reflect the categories of narratives on the topic under study and their manipulative potential.

According to a 2023 study conducted by Columbia University researchers, 59% of social media links shared by users are never followed. According to the researchers, most readers only read the headline. Previously, similar studies had been conducted. The proportion of people who only read news headlines has fluctuated over time, but it has always been the majority in the sample.

The data was analyzed using Microsoft Office Excel and a formula that determines the manipulative potential of each news item based on the parameters specified. Three expert assessments, a fact-checking coefficient, and a coefficient of topic relevance in the context of direct impact on bilateral relations were among the parameters used to calculate the manipulative potential of each news headline. Following the creation of a raw data summary table, the manipulative potential was calculated by multiplying the average value of expert assessments of the headline’s manipulative nature (from 0 to 10) by the probability coefficient (based on fact-checking conducted by the study’s authors) and the relevance coefficient (based on the rating of topics by their importance for Poland and Ukraine (event analysis) presented in RT’s content). As a result, the final value is calculated as the product of the average score, reliability score, and topic rating at the end. Given that the coefficients’ values can be zero according to the terms, a value of 0.1 was added to each coefficient when the formula was applied.

The final equation:

The total score (Lx) equals the average score (Ix). * Fact-checking coefficient (Jx+0.1) * Rating coefficient (Kx+0.1), where L, I, J, K represent column numbers and x represents row number (from 3 to 1074)

The „preliminary” data is available here.

The authors’ assessments were used to rate the topics.

To calculate the rating, the topics covering Ukrainian-Polish relations were divided into the following groups in descending order based on the possibility of real influence on both countries’ political discourse:

1. Ukrainian refugees, extradition to Ukraine, „Banderivtsi,” migrants (because it puts people in direct danger on a daily basis). The topic was identified as a priority due to the potential to quickly radicalize society’s mood and negatively affect intergroup dynamics, particularly given Poland’s pre-election period (10);

2. Supplies of arms to Ukraine. The topic has been identified as critical due to Poland’s ever-increasing role in increasing arms supplies to Ukraine (9).

3. Ukraine-Poland cooperation (transit of Ukrainian goods), potential aggression, and seizure of western territories. The topic is deemed critical because it has the potential to harm bilateral cooperation by eliciting reactions from all segments of the population, potentially leading to a general deterioration in bilateral relations (8).

4. Ukraine’s President, Volodymyr Zelenskyy. The topic is defined as critical due to the general focus of Russian information resources on discrediting the presidency as a power institution in Ukraine, as well as the use of technologies to discredit the reputation of „inconvenient” politicians in numerous Russian Federation information influence operations (7).

5. The German factor. The topic is significant in light of the possibility of radicalization of contradictions between Poland and the EU, and as such, it can fuel Russia’s strategic interest in inciting conflict within the European Union (6).

6. The downing of the Polish missile. In the context of the Ukrainian war, the implications of the Ukrainian war for Polish society, and the decisions that the Polish authorities must make. The topic was chosen because of the potential for societal frustration. However, given Poland and Ukraine’s high level of solidarity, manipulation of this topic will have no immediate negative consequences (5).

7. Polish demonization concerning Ukraine and the West. The topic is defined as negative, but not capable of causing sudden negative crisis situations (4).

8. The Belarusian factor. The topic is defined as negative, but only because it already has a significant negative connotation for the audience and the public perception of narratives on this topic (3).

9. Demonization of the West concerning Poland by the United States, NATO, and the European Union. Because of the high level of abstraction in Ukrainian-Polish relations, the topic of demonization of the West is defined as negative, but not capable of causing a crisis in the short term (2).

10. Russia, relations with Russia, USSR narrative, „Russophobia.” The topic is defined as negative, but only because it already has a significant negative connotation for the audience, as evidenced by public perception of narratives on this topic (1).

11. Other (0).

3.2 Research results

Taking into account the rating coefficient, the following ten news items from the Russian holding RT have the greatest manipulative potential, according to the study’s findings.

The following are the headlines in the original language:

- Власти Польши заявили, что не планируют продлевать помощь украинским беженцам;

- Экс-разведчик США Риттер: миллионы украинцев сбегут в Польшу после поражения ВСУ;

- Myśl Polska: поведение украинских беженцев показало необходимость денацификации Украины (опубліковано у стрічці RT із зазначенням зовнішнього ресурсу, відповідно Myśl Polska);

- Myśl Polska: в Польше призвали вернуться домой бандеровцев, приехавших с Украины (опубліковано у стрічці RT із зазначенням зовнішнього ресурсу, відповідно Myśl Polska);

- Гагин: другие страны вслед за Польшей начнут выдавать уехавших с Украины мужчин;

- WolnośćTV: в Польше украинцы избили поляков, заставив их кричать „Слава Украине”;

- Rzeczpospolita: Польша начала выдавать Киеву уехавших с Украины мужчин

- Myśl Polska: не менее 10 тысяч поляков погибли в конфликте на Украине

- Портал Lublin112 рассказал, как украинские беженцы „захватили” польский Красныстав;

- Экс-советник Пентагона Макгрегор: Польша может стать участником конфликта на Украине.

The majority of headlines about Ukrainian refugees received scores ranging from 93 to 107, with a maximum score of 107. Headlines on sensitive historical topics (the Volyn tragedy), historical revanchism (Poland’s plans to „capture” western Ukraine), and doubts about the importance of friendly relations between Ukraine and Poland range from 80 to 93. There are headlines in the 70s and 80s that broadcast narratives aimed at the Polish target audience, discrediting President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and spreading doubts about the wisdom of contributing to Ukraine’s arming.

The headlines of news stories about stirring up regional contradictions around Poland in the EU, as well as grain transit, range from 50 to 70. It is worth noting, however, that topics relating to the transportation of Ukrainian agricultural products are more prevalent in the lower ranges, indicating that the Russian state propaganda machine is likely to face difficulties when it is required to react quickly to unforeseen situations.

Thus, the topic of Ukrainian grain, while negative in comparison to the general information context between the two countries, has a lower manipulative potential than the topic of Ukrainian refugees, and it is less harmful in a crisis. The headlines of news reports about the Belarusian factor, the fall of missile remnants on Polish territory, and the escalation of the so-called entry of Poland into the war range from 20 to 50. There are headlines in the 10-20 range about so-called Russophobia, emphasizing the contradictions between Poland and Lithuania and utilizing the Belarusian factor. Topics ranging from 0 to 10 include the transit of Ukrainian grain, individual cases of arms supplies, and discrediting the EU. Sports news has the lowest potential for manipulation.

The findings of this study are only relevant in the context of bilateral relations between Ukraine and Poland during Russia’s full-fledged aggression against Ukraine, as well as taking into account the Polish parliamentary elections, which created a corresponding configuration of information priorities in both Ukrainian and Polish society.

3.3 Recommendations and Conclusions

SWOT analysis of Russian information influences on Ukrainian-Polish relations in 2022-2023

S

Immigrants from Ukraine and Belarus in Poland are both targets of information attacks and a channel for Russian information influences transmitted via language communication by Russian-language information sources. Furthermore, the Russian information influence system employs a vast ecosystem of vertical distribution of information messages via social networks, anonymous platforms (Telegram), and local platforms to ensure total information influence. The effectiveness of the branched toolkit, on the other hand, can only be seen in the dissemination of topics with high manipulative potential.

W

The Russian information influence’s weakness in these circumstances, as well as in the information contexts of Ukraine and Poland, is often due to the lack of an ad hoc response to sensitive and unpredictable topics, particularly when it comes to highly specific issues of bilateral relations or the technical resolution of certain issues. This can benefit Ukraine and Poland in jointly countering information threats, as long as they continue to develop joint countermeasures to Russian information influence.

O

Russian information influences in the context of bilateral relations can create new opportunities for promoting Russian narratives by simultaneously influencing Ukrainian and Polish society through the manipulation of sensitive topics. The demonization of Poland in the eyes of the EU, as well as the spread of the anti-European narrative, are also dangerous in this context, though they do not have a strong manipulative potential for Polish society as a separate topic, but can be a reinforcing element in the appropriate configuration.

T

Mutual integration of Ukraine’s and Poland’s information spaces, as well as the presence of Polish experts in the Ukrainian and Ukrainian information spaces, may pose a challenge to the effectiveness of Russian information influence. This challenge can be met by incorporating Ukrainian (and Belarusian) refugees into the mechanism for countering Russian information influences, as well as by deploying joint countermeasures with Ukraine.

General conclusions:

- One of the main dimensions of Russia’s external information influence is the destruction of relations between neighboring states. For this purpose, a wide range of tools of information influence on the humanitarian environment of another state is used, aimed at destabilizing the political process and provoking social tensions. Since the 1990s, Russia has consistently used these practices to create a belt of instability around the Kremlin’s geopolitical ambitions.

- In the system of Russian information influences, we can distinguish between metanarratives, narratives, and information messages of varying degrees of truthfulness. Metanarrative forms are widely used by Russian propaganda in different countries’ information spaces, taking into account local peculiarities in different political, social, or economic contexts, to shape the audience’s attitude toward certain events and influence the audience’s behavior in the future. Each metanarrative is implemented through a series of specific narratives, which are made up of information messages with varying degrees of veracity.

- Undermining Ukraine’s relations with its partners is a strategic goal of Russian propaganda in a full-scale war. The topic of Polish-Ukrainian relations is a particularly relevant area of Russian propaganda aimed at disintegrating Kyiv and its partner countries. Given the importance of Poland’s and the Polish people’s military, diplomatic, logistical, and economic assistance to Ukraine, stagnation in Warsaw-Kyiv relations has a direct impact on the strategic situation. Moscow is escalating conflict situations in the media between Poles and Ukrainians, attempting to distort the image of the two countries and peoples in each other’s eyes. In this way, the Kremlin hopes to attack Ukraine’s economic backbone by undermining Ukrainians’s trust in Poland as a safe place to live and work.

- Russia has rather limited tools to influence the Polish audience due to the language barrier. Therefore, people from Russian-speaking environments (primarily Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Russians) are the most vulnerable to manipulation, and Telegram will continue to be the primary platform for spreading anti-Polish narratives. As a result, Russia is attempting to influence Poland’s sociopolitical stability indirectly through national minorities.

- Russia’s tactics are characterized by a flexible approach to the selection of topics for manipulating public opinion (but a much lower efficiency in their use (ad hoc) in crisis situations). The adaptability of Russian propaganda lies in exploiting pre-existing (national memory) and current (grain transit) contradictions between Poland and Ukraine. At the same time, a number of the main anti-Ukrainian messages that Moscow uses to discredit Ukraine among Western European societies or in regions of the Global South (for example, about the „Nazi regime in Kyiv,” „oppression of Russian speakers by Ukrainian authorities,” „the conflict provoked by the United States to weaken Russia,” etc.

- Russia actively covers the activities of Polish right-wing radical organizations and parties. Moscow’s information activities contribute to the radicalization of a segment of Polish society, indicating an attempt to directly influence Polish domestic policy. The main resource in this regard is the history of Polish-Ukrainian relations and anti-American ideas.

- Moscow has been focusing its efforts on creating and promoting the anti-war movement in Poland since the start of its large-scale aggression against Ukraine. In fact, these types of organizations serve as platforms for the consolidation of anti-Ukrainian forces in Polish politics, as well as a tool for inciting interethnic conflict.

- Russia is attempting to simultaneously influence Polish and Ukrainian societies to sow discord and distrust between the two peoples. At the same time, we can see the Russians’ desire to polarize public opinion in Poland and Ukraine in areas of common interest. Our analysis revealed that the most common anti-Ukrainian narratives aimed at the Polish audience include the following: „Warsaw’s military intervention in the war,” „Poland is „profiting” from the war,” „Intimidation of Ukrainian refugees by the radical policy of the Polish authorities,” and „Poland’s plans to occupy Ukrainian territory.” Among the key narratives that Russia incorporates into the Polish information space in order to discredit Ukrainians and provoke ethnic hatred are the following: the situation of Ukrainian refugees, including problems of adaptation, domestic conflicts, „infringement” of the rights of Poles due to the growing number of Ukrainians; historical memory and historical revanchism, the threat of increasing Ukrainian influence on Polish politics (slogans about the so-called „Ukrainianization/Banderization” of Poland).

Recommendations:

- It is recommended that a bilateral mechanism for recording Russian information influences on the topic of Polish-Ukrainian relations be established. The joint platform should include media experts, media representatives, and specialized think tanks. Continuous monitoring of the information environment in Poland and Ukraine should be aimed at recording coordinated Russian campaigns aimed at discrediting the two countries’ existing achievements and potential for cooperation. Simultaneously, it is critical to limit the impact of the current political situation and agenda of Polish-Ukrainian relations on the activities of the respective analytical platform.

- It is critical to concentrate efforts on minimizing the potential impact of Russian information operations on strategic areas of Polish-Ukrainian relations (arms supply logistics, Ukrainian security and rights in Poland, trade and economic policy, and so on). When analyzing one of the countries’ positions on an issue that has sparked debate or has the potential for conflict in Polish-Ukrainian relations, the possibility of Russian information interference or provocation should be considered.

- Exposing Russian influence actors operating in the Polish media space is one aspect of information protection. Countering the incorporation of pro-Russian influences into the Polish information environment should be a comprehensive concept that includes legislative regulation, increased control by security sector institutions, and civil society oversight. The authors propose the following countermeasures: marking Russian propaganda theses as part of nationwide measures to increase society’s information resistance; increased control by special services over pro-Russian platforms within social networks; and a review of academic exchange programs in the scientific and educational spheres in light of Russia’s ability to spread information influence.

- In the context of Russia’s efforts to transform its information presence into political influence, restrictions on Russian information resources should include not only a direct ban on broadcasting but also access to sensitive Polish-Ukrainian relations information. It is also necessary to combat the tendency of Polish right-wing radicals and other „out-of-system” organizations to align with the pro-Russian agenda in the information sphere.

- Continually inform Ukrainian citizens residing in Poland about the government’s current policies and plans regarding their status, rights, and security, among other things. This will help to avoid Russian manipulations and forgeries intended to „discredit” Ukrainians in Poland.

- Avoid politicizing national memory and using history in political campaigns. It is recommended that both countries’ media cover and popularize common pages of history, successful examples of modern cooperation, and potential economic projects for Ukraine’s reconstruction. This will invalidate the majority of the narratives created by Russia to distort the image of Poles among Ukrainians.

Terms employed

Adaptive Narrative – a narrative structure for organizing experience or presenting facts (story) that can interact with various information contexts and environments.

Addressee (recipient) – the person to whom an information message is addressed is known as the addressee (recipient).

Active Measures (measures of assistance) – a set of practices that include disinformation, activities of agents of influence, and quasi-public organizations to exert pressure on other states.

Audience (target audience) – a group of people (addressees) who share certain characteristics, information interests, and needs and are potential consumers of a specific narrative.

Public Opinion – a collection of judgments and assessments that represent society’s overall position; it is a socio-political phenomenon that reflects the general will.

Hybrid Threats – actions taken by state or non-state actors with the intention of undermining or harming an object by influencing decision-making at the local, regional, national, or institutional levels. Such actions are coordinated and synchronized, and they are designed to exploit the weaknesses of democratic states and institutions. Activities can take place in the political, economic, military, civilian, or information spheres, for example. They are carried out using a variety of methods in order to stay below the detection and attribution thresholds.

Sharp Power – a type of hard power that involves the use of tools to manipulate public opinion in other countries.

Destructive Information Influences – external destructive information influences on the public consciousness through the media and the Internet with the aim of undermining the constitutional order, sovereignty, territorial integrity and inviolability, as well as promoting separatism, interethnic and interreligious hatred.

Disinformation – inaccurate, false information disseminated by state or non-state actors with the intent to mislead the audience, with the risk of forming a distorted perception of state policy and increasing tension during emergencies or armed conflicts.

Information Warfare – 1) aggressive interference in a country’s or a group of people’s (audience) information space in order to change their picture of the world in their own interests; 2) actions taken to achieve the information advantage of one’s own military strategy through influence on the enemy’s information and communication systems while ensuring the security of one’s own information resources.

The Information Space – a coordinated, multi-level space in which information is created, moved, and assimilated, as well as the outcomes of society’s communication activities.

Cognitive Distortion – a systematic error in thinking that influences people’s judgments and decisions. Such biases are especially noticeable in uncertain situations. They are frequently caused by your brain’s attempt to simplify information processing. As a result, our decisions are neither rational nor objective.

Manipulative Potential – a set of capabilities to shape the audience’s perception of certain events by abstracting and concretizing the metanarrative and narrative in accordance with the local communication context and the interests of the Russian Federation using state propaganda and soft power.

Metanarrative (grand narrative, geopolitical narrative, systemic narrative) – a public myth that summarizes dominant social perceptions and official versions of the past, present, or future.

Soft power – the ability of a state or government to achieve its goals through its own attractiveness.

Narrative – a structure, a construction for organizing experience or presenting facts; a story (narrative) that forms an idea of the world, of the norm, of deviations from the norm, and defines markers of „friend or foe.”

Propaganda – a systematic communication (pseudo-communication) activity aimed at manipulating people’s beliefs, attitudes, actions, and/or spreading doubt, using symbols, words, gestures, cultural models, and characterized by selectivity in shaping discourse, attempts to control it, and exploitation of stereotypes and presuppositions that exist in society and are fueled by established ideology. A characteristic feature of propaganda is epistemological manipulation, which distorts the ability to establish cause-and-effect relationships by replacing the rational (thinking) process with irrational (emotional) impulses and leads to cognitive distortions.

Fake – the presentation of facts in a distorted form or the presentation of deliberately false information.

The report was written by Marianna Prysiazhniuk and Volodymyr Solovian, experts of Ukraine Crisis Media Center (UCMC) in collaboration with INFO OPS Poland Foundation (Poland).

The following experts and think tanks contributed to the report’s creation:

- Yevhen Magda, PhD in Political Science, Associate Professor of Ukraine’s National Technical University „Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute”, Director of the Institute of World Policy, iSANS expert;

- Taras Zhovtenko, PhD in Political Science, Associate Professor of Ukrainian Catholic University’s Department of Public Administration, security analyst (international security, defense) in Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiative Foundation;

- Pavlo Kryvenko, Head of the Artificial Intelligence and Cybersecurity Section at the New Geopolitics Research Network, provided technical assistance with the methodology’s development.

- Stanislav Zhelikhovsky, PhD in Political Science, international expert;

Public task financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland within the grant competition “Public Diplomacy 2023”

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the official positions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland.